Pagan Multiplicity and Ecological Challenges

By Neha Khetrapal (Jindal Institute of Behvaioural Sciences)

In this comment piece, Dr Neha Khetrapal reflects on the interactions between climate change and religious traditions. Several pertinent questions emerge in the midst of the reflection: Can ‘human exceptionalism’ lead us away from conservation? Will the world witness a new religion at the end of the Anthropocene Epoch? If there is hope for a more nature-friendly religion, will we have new symbolising deities, mermaids?

Neo-Paganism in the Present and of the Future

A family visits a non-frequented island in the Indian subcontinent where they witness waves crashing on the pristine beaches, strewn with rocky capes. The preschooler on holiday thinks aloud that the rocky capes need to bathe and hence, waves are present in our world. The child’s description gives us a peek into our tendency to understand nature and naturally occurring entities as intentionally designed, irrespective of our age. We may be inclined to label the agentive intentional stance as primitive in nature in contrast to the physical-causal mechanistic explanations. However, ontogenetic development paints a different picture. If children have recourse to agentive conceptualisations, then this reasoning may have significantly coloured our worldview, especially in times when pedagogy was not targeted at overcoming such forms of thinking in classrooms.

Untutored human tendency to ascribe purpose to natural phenomena has inspired investigations of natural reality over our evolutionary history and most likely culminated into nature worship when religious traditions began to take shape. With the expansion of agricultural practices approximately 6,000 years ago and the associated forest clearance, the pagan ideas of an animated and defied nature, reminiscent of the hunter-gatherer cosmologies, gradually receded to the societal fringes. As the race for cultivation intensified and the industrial revolution took hold, religious traditions and ideologies underwent changes as well. The birth of Abrahamic religions, with a tacit emphasis on a discoverable order for nature, highlighted ‘human exceptionalism’. Technological advancement of the modern world further bolstered the special value that societies attached to humanity.

In the aftermath of worldly changes, the post-agricultural communities have served as harbingers of ‘Anthropocene' in sync with the privileged ‘human status’. Climate change that has taken place in the Anthropocene Epoch and has the potential to transform the heavens above calls for a radically different worldview, which emphasises the supremacy of nature. The search for order and meaning has diversified into three different socio-religious domains. First, the rejection of Abrahamic religions in a few pockets has given way to environmentalism. People in several parts of the world, like Scandinavia, have embraced paganism, underscoring the divinity of nature. Second, the distinction between the natural and the supernatural is softening within established religions and giving way to considerable ‘greening’ and ‘bluing’ in sections of Christianity and Hinduism, among other religions. Third, there has been an increased focus on indigenous people who live in harmony with nature. Inspired by their religious beliefs, local communities have maintained our planet’s biodiversity hotspots for millennia. As such, wildlife-rich forests and freshwater resources are confined to religious sites when compared to the ongoing degradation of other ‘natural’ areas. On parallel lines, destruction of sacred groves has intensified in areas witnessing a high rate of religious conversions from tribality to Christianity e.g. the Indian states of Mizoram and Manipur.

Image 1: A scene from 1973, from Northern India, where the Chipko Movement took birth

The urgency to protect the wilderness has given way to community-based protection of biodiversity hotspots. In most of these cases, vigilance efforts are unaccompanied by the sacred sentiments of the historic era. A notable example includes the Chipko movement (that literally translates into “tree hugging”) by the indigenous people residing at the foothills of Himalayas as a peaceful protest against deforestation. The movement was initiated as a means of preserving native ownership of the forest lands and the indigenous lifestyle (see, Picture 1). Gradually, the uprising spilled to several states of India and was noted for its influence on the reformulations of natural resource policies in India. Due to its success, the Chipko Movement served as a catalyst for a variety of environmental protection movements in India. Parallel indigenous movements have also been reported from other parts of the world like Brazil and Indonesia. The movements have, at the least, etched the strong interdependencies between humans and nature for the rest of the global population. Correspondingly, statistics from the Amazon Basin show that rates of deforestation are lower in tribal territories, where governments have acknowledged collective land rights.

Paganism in the Anthropocene Epoch

In anomalous manners, technological progress of the contemporary times has rekindled human fascination for the agentive natural forces. Advanced technical know-how and accumulated scientific knowledge have failed to arrest the spread of zoonotic diseases or rising sea-levels. Shaken by the failure of human supremacy, the post-industrial civilisation is in search of a new social order to reconstruct its worldviews and to infuse hope for a better habitat. The search has motivated some to embrace environmentalism as their new religion, precipitated ideological changes for the followers of Abrahamic religions, whereas for others, the quest entails paying more attention to the indigenous voices. From the perspective of scholars who study religion, these socio-religious changes could be broadly classified as non-indigenous and indigenous neo-Paganism.

Image 2: Kalpataru, the divine tree of life, at the 8th century Pawon temple in Java

The current that unites all neo-pagans hinges on rebuilding humanity’s relationship with nature. A few decades from now, it is plausible that the world will witness both ecological and religious changes concomitantly. Our ancestors have had their share of tumultuous changes and have bravely survived the dynamics. Based on the success of the past, it is viable to anticipate that current and future generations will brave anthropogenic changes as well.

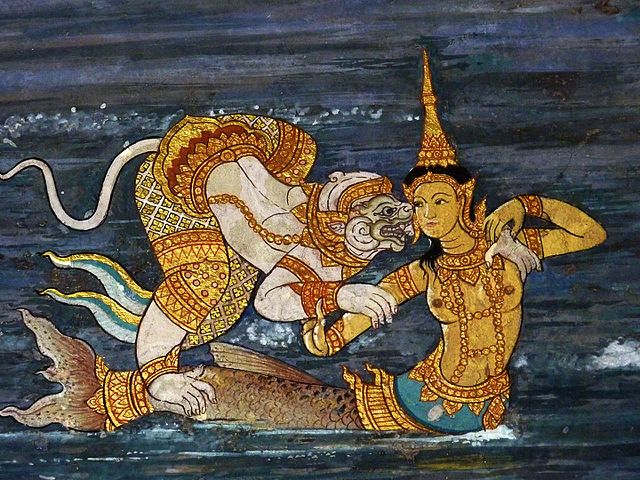

At the end of the anthropogenic tunnel, lies a greener and a bluer tomorrow and an exciting new religious terrain to fathom (see, Figure 2). Neo-paganism with its myriad shades and myriad terminologies (eco-spiritualities and eco-theologies), could thus be conceptualised as the new religion or a new form of spirituality for societies facing ecological challenges. There are several interesting questions for religious scholars that remain unanswered. Would neo-paganism involve re-interpretations of ancient rituals and traditions or re-naming of ancient deities like mermaids, that symbolise human-nature interdependencies (see, Figure 3)? Are neo-pagans working towards extending the Western notions of kinship to include the planet? Do these strivings set the Abrahamic religions apart from neo-paganism? Will the spread of neo-paganism lead to a decentring of the human position in the ecosystem with the consequent decline of human exceptionalism? In the interim, kinship with nature, which is socially packaged as spiritual or religious orientation to the natural world, will continue to challenge human exceptionalism.

Image 3: Suvannamaccha, the mermaid princess, appearing in the Thai and other Southeast Asian versions of the ancient Indian Epic, Ramayana

In a nutshell, the religion of the future promises to reconcile our estranged relation with natural entities and open opportunities for everyone, not just children, to unleash their agentive intentional predispositions. The human quest for a new social order may end in the future or may continue to evolve in response to the unique challenges that each epoch would present. Until then, it is easy to see how ideologies about human interconnectedness with the natural world constitute the fundamental plank of neo-paganistic religious beliefs and worldviews. To the environmental psychologists, these beliefs and worldviews are worth investigating for their potential to precipitate climatic actions and other conservation efforts.

References

Image 1: A scene from 1973, from Northern India, where the Chipko Movement took birth. Source: NA, CC BY-SA 4.0. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chipko_movement#/media/File:Big_chipko_movement_1522047126.jpg

Image 2: Kalpataru, the divine tree of life, at the 8th century Pawon temple in Java. Source: Photo by Gunawan Kartapranata / CC BY-SA 3.0, retrieved via, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kalpavriksha#/media/File:Kalpataru,_Kinnara-Kinnari,_Apsara-Devata,_Pawon_Temple.jpg

Image 3: Suvannamaccha, the mermaid princess, appearing in the Thai and other Southeast Asian versions of the ancient Indian Epic, Ramayana. Source: Photo Dharma from Sadao, Thailand, CC BY 2.0. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Suvannamaccha#/media/File:072_Ramakien_Murals_(9150815520).jpg