F&A Series: Branding, labeling and (re)storing - Conservative Christian food activism in South Africa

Dr. Hans Olsson is a Marie Curie fellow at the Centre of African Studies, University of Copenhagen. He is currently working on a project on the interplay between Christianity, farming and environment in South Africa funded by Horizon 2020, European Union. His research interests are currently in the intersection of religion, culture and nature.

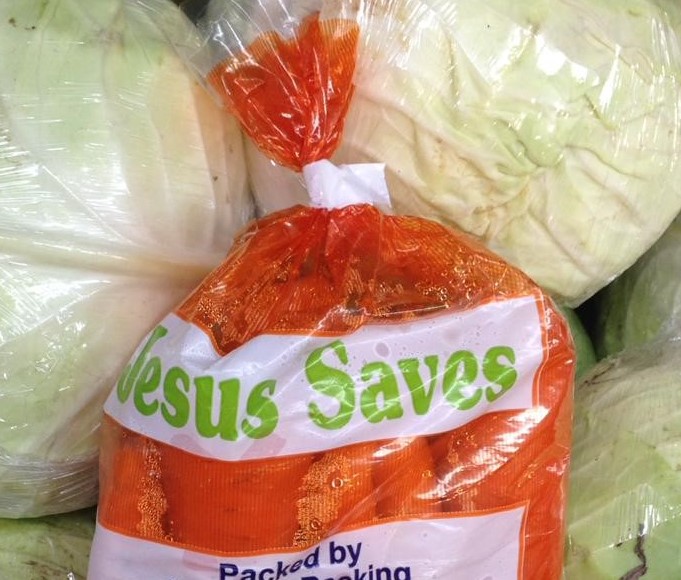

What we eat and how we consume food reflects values, identities and beliefs. While many religious traditions have strict rules on what to consume and how to handle food, Christians’ food rules have remained sparse. But that does not mean that food is absent from how Christians’ express their faith. During recent fieldwork in the Eastern Cape,  South Africa, my weekly purchase of carrots were labeled “Jesus Saves”. What did this message, purchased in one of South Africa’s large supermarket chains, imply? Was it the farmer’s way of evangelizing, of witnessing faith in public? A way of branding the product Christian, that the carrots are grown in a righteous way?

South Africa, my weekly purchase of carrots were labeled “Jesus Saves”. What did this message, purchased in one of South Africa’s large supermarket chains, imply? Was it the farmer’s way of evangelizing, of witnessing faith in public? A way of branding the product Christian, that the carrots are grown in a righteous way?

How food (consumption and production) relates to conservative forms of Christianity in contemporary South Africa also caught my attention while researching sustainable farming promoted by Evangelical/Charismatic Christians. Their focus on environmental stewardship, endorsing sustainable living by restoring depleted farmlands, to some extent blur categorizations between “conservative” and “progressive” Christian expressions, and also challenges the lines between Christian witness (as evangelism) and activism.[i] Here, I approach public performances of Christian witness as forms of activism,[ii] and take food as a window into how Christian faith are performed (and contested) in South Africa public today.

On such example occurred in 2012, when a Christian voluntary organization brought the South African government to court over the presence of religiously certified food. The petition argued that regulations for branding food, and Muslim halal certification in particular, discriminated other religious traditions. Backed by campaigns through social media platforms Christians criticized the presence of halal certified food products in South African supermarkets—ranging from sparkling water at Pick’n’Pay to the popular Easter treat, hot cross buns, at Woolworths—to enforce South African’s Christian majority to support Islam through the consumption of food. To some extent, the protests forced supermarkets to adjust the amount of halal certified food. It also caused Christians to act, launching a Christian food brand, Christian Friendly Products, as a Christian alternative to the Muslim halal certification in 2014.

While “Christian Friendly Products” remain limited in outreach, with just a few  companies and supermarkets so far labeling products with the brand, it nonetheless highlights how food consumption reflects what it means to be a Christian. Food become spaces where Christianity is performed in opposition to Islam but also reveals how Muslim food certifications influence the ways through which Christians’ appropriate food as a means of faith-based activism in public. Such appropriations is also present in relation to food production.

companies and supermarkets so far labeling products with the brand, it nonetheless highlights how food consumption reflects what it means to be a Christian. Food become spaces where Christianity is performed in opposition to Islam but also reveals how Muslim food certifications influence the ways through which Christians’ appropriate food as a means of faith-based activism in public. Such appropriations is also present in relation to food production.

Nelson Mandela Bay today serves as a regional and international hub in the promotion of what is called Farming God’s Way (FGW)—a Christian approach to produce nutritious and healthy food. Originating in Zimbabwe in the 1980s, FGW views agriculture as part of bringing hope and progress to the “poor, the hungry and the broken.”[iii]Systematized and extended by a network of born again, primarily white, South Africans,[iv] the model promotes agricultural technologies (do not plough, apply mulch cover, and practice biodiversity) and management rules (on time, to high standards, without wastage) based on how God, the “Master Farmer”, envisioned fertility and sustainability in creation. Based on a vision of environmental stewardship, FGW manifests in taking “the Sunday worship into the Monday farming”[v] and materializes in the cultivation of productive gardens, meticulously laid out in perfect matrix of  vegetable crops.

vegetable crops.

FGW labels food production as part of a righteous Christian life-style, which serves to evaluate farming practices between “God’s way” and “human’s ways”. Such distinctions not only serves to criticize conventional agriculture methods (ploughing in particular), but also traditional African practices on the land. It situates land as cursed, caused by deep soil ploughs and/or ancestral worship, which prevents people from properly engage and realize the God-given potential for cultivating food. In this wider critique FGW sees, government grants, NGO’s inputs and Churches’ mercy ministries, as part of a dependency syndrome that keep (poor) South Africans from engaging in the work needed to transform their lives.[vi] Farming God’s Way sheds light on how contemporary Christian activism enters debates on food production, food security and sustainable living by endorsing change through the restoration of divine order. Situated against conventional farming methods FGW could be viewed part of progressive alternative. Yet, with the model situated in one of the world’s most unequal countries, FGW’s war on traditional practices—distinguishing the saved from the lost, the knowledgeable from the ignorant, and the responsible from the lazy—rather tends to (re)produce conservative positions of race, gender and class in South Africa today.

Providing a window for how Christian faith practices and activism are enacted in relation to the consumption and production of food in South Africa this piece unfolds how Christian activism takes place in supermarkets, on farms and over the use of the land. It provides glimpses of how particular forms of Christian witness materialize in South Africa’s public arena today. While they all tend to sharpen boundaries of what is considered Christian practice and not, these forms of faith-based activism, their calls for restoration and change, also highlights how contested political economies of the sacred[vii] are embedded in the materiality of food.

Written By: Dr. Hans Olsson

Image Credits: Dr. Hans Olsson (feature and in-text)

Footnotes:

[i] In the growing academic field that addresses the interplay between religion and environmental sustainable living, there is a tendency to focus on “progressive” religious groups with a liberal, political left agenda. See for example LeVasseur, T. 2017. Religious Agrarianism and the Return of Place: From Values to Practice in Sustainable Agriculture. Albany: State University of New York Press and Van Wieren, G. 2018. Food, Farming and Religion, Emerging Ethical Perspectives. London: Taylor and Francis.

[ii] Here I follow John Fletcher’s work stressing that Evangelical/Charismatic Christian outreach should be seen to parallel other forms of activism in their urge to create convince other to change. See Fletcher, J. 2013. Preaching to Convert: Evangelical Outreach and Performance Activism in a Secular Age. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, p. 3.

[iii] Farming God’s Way draws heavily on the bible verse Isaiah 58 where the meaning of the “true fast” is unfolded—that is, caring for the poor, clothe the naked and feed the hungry.

[iv] The extension of the model is mainly done through written guidebooks, DVD’s and tutorials available on YouTube. The movement also arrange physical workshops and have a program to train people to become accredited trainers, which could then extend the model into new contexts.

[v] Interview with Farming God’s Way trainer 2020-04-03.

[vi] A recurring example brought forward by the FGW is the area Transkei, where up to 90% of good farmlands is viewed to remain idle.

[vii] For more on the political economies of the sacred in South Africa see Chidester, D. 2016. Wild Religion Tracking the Sacred in South Africa. Berkeley: University of California Press.

This blog post is part of a project that has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 843798.