Reconnecting Jewish History in Leeds

Alan Benstock is a student in the master's programme Religion and Public Life at the University of Leeds. In this blog post, he shares some of his findings of a research project he was involved in focusing on reconnecting artefacts in the Leeds Museum to the history of the Jewish community in Leeds.

The Jewish community is often portrayed as arriving in Leeds during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century to escape the pogroms and anti-Jewish violence in the Russian Empire and Eastern Europe. Whilst the flood of immigration resulted in the sudden and dramatic increase in the Jewish population, Jews are recorded as living in the city one hundred and fifty years earlier in the mid-eighteenth century. The first Jewish cemetery was opened in 1840 and is generally regarded as when the community became established. Jewish Orthodox tradition does not require collective worship to take place in any prescribed building or location only the presence of a Minyan - ten men over the age of 13 - for the recitation of certain prayers. It is for this reason that is was not until twenty years later in 1860 that the first purpose-built synagogue was built in Belgrave Street in the city centre.

Despite the relocation of the Jewish community into the suburbs of North Leeds during the following century, this synagogue remained in use until 1986 when it was closed, along with the synagogue on Chapeltown Road – built in 1936 now the Northern School of Contemporary Dance - and Moortown Synagogue. The three congregations came together in a new purpose-built synagogue on Shadwell Lane, collectively adopting the name: United Hebrew Congregation (UHC). Whilst a significant number of architectural features from each of the three synagogues were incorporated into the design of the new building including 150 stained-glass windows and the pulpit, over ninety items were donated to the Manchester Jewish Museum. Following a decision by the Manchester museum to concentrate its collection on Jewish communities of the Manchester city region, these artefacts were relocated in 1990 to the Leeds Museum.

The UHC congregation holds many collections of documents and papers from each of the three congregations including correspondence, minute books, annual reports and books of accounts the oldest of which dates back to 1880. Whilst some have been bound into books, there is currently no index or catalogue nor any planned approach to storage.

With the assistance of a small grant from the Leeds Museums and Galleries (LMG) / University of Leeds Cross Disciplinary Innovation Fund, a pilot research project titled “Connecting faith Collections with faith communities” was undertaken this year. One of the aims of the pilot is to see if, by looking at the documentary records held by UHC, whether the artifacts held by LMG could be put into both a religious and social context; adding to the provenance of the objects and producing an additional educational resource.

Seventy items in the LMG collection, recorded as being part of those transferred for the Manchester Jewish Museum in 1990, were selected for consideration. Of the records held by the UHC, three collections were used in the research - half-yearly accounts and accounts from 1880 to 1930; community bulletins for the period 1936 to 1939 and minute books from the 1920s.

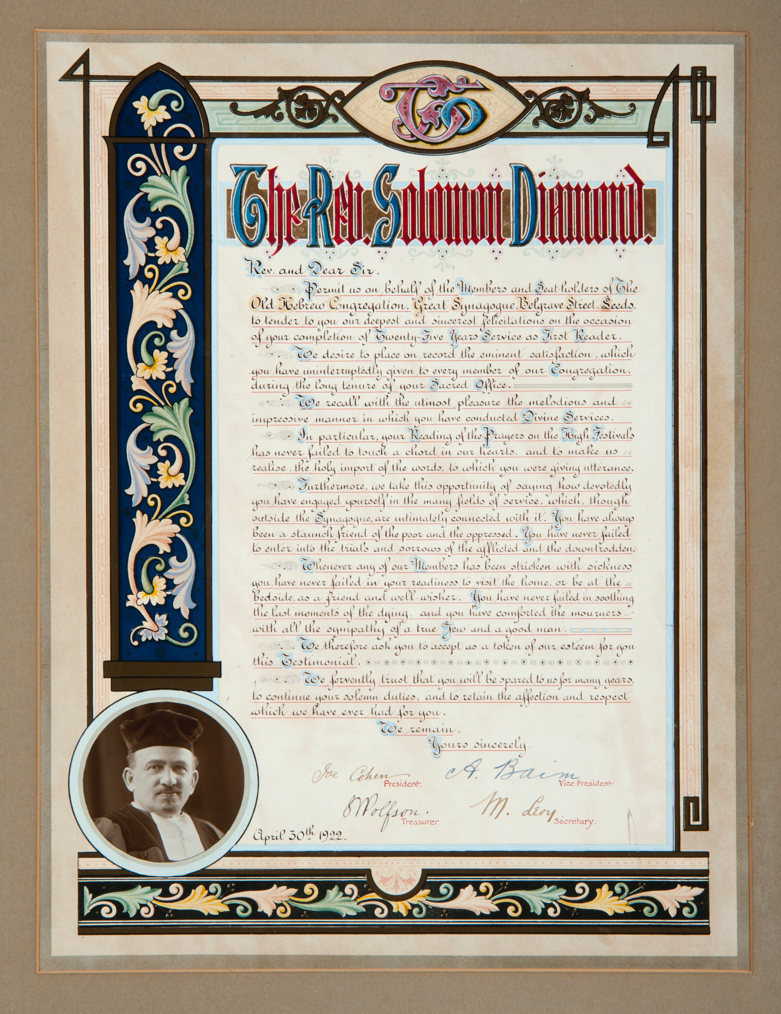

One item – pictured to the left – is an example of an artefact successfully reconnected to the community. The current description in the LMG catalogue reads:

Illuminated address, with grey card mount, presented to Rev. Solomon Diamond by the Old Hebrew Congregation, Great Synagogue, Belgrave Street, Leeds on the occasion of his completing 25 years as first reader; signed by the President and other officials; in bottom left corner is inset photograph of Rev. Diamond, dated April 30th 1922

There are a number of references to this presentation in the UHC documents, including:

(1) From May 10th, 1922 minute book:

Agenda item 1 - Final arrangements for presentation to Rev Diamond. The following was recommended to the General meeting that the Rev Diamond be the recipient of a minimum of £150 and testimonial and gold watch. The details of the reception were discussed

(2) Balance sheet and reports 13th November, 1922 p4:

The Rev S Diamond having completed twenty-five years’ service as Reader, the Congregation felt it a great pleasure to mark the occasion by presenting Rev Diamond with a fitting testimonial. A large gathering assembled at the rooms of the Jewish Institute in July 1922 last, over which Guardian J Cohen the President presided, when the Rev Diamond was the recipient of an Illuminated Address, accompanied by a cheque and Gold Watch suitably inscribed. All the speakers on that occasion eulogised the work done by the Rev Diamond

The accounts (pictured to the right) detailed that the cheque presented was for £150 (at today’s values £6975) and the gold watch together with the illuminated scroll cost £23 13s 6d (£1100.89).  These gifts were funded by members’ donations totalling £152 1s (£7070.33) a grant from Synagogue £20 7s (£946.28) and bank interest £1 5s 6d. The members’ individual contributions are detailed in the accounts and reveals an apparent hierarchy within the congregation.

These gifts were funded by members’ donations totalling £152 1s (£7070.33) a grant from Synagogue £20 7s (£946.28) and bank interest £1 5s 6d. The members’ individual contributions are detailed in the accounts and reveals an apparent hierarchy within the congregation.

Access to the records and documents used in this research would not have been possible without me being a member of the UHC Council. The failure to specify in the project proposal which voices are to be heard meant my need to be “objective and detached” in this academic research conflicted with my role as a representative of the UHC synagogue.

The impact of such lack of specification is illustrated when considering possible narratives for item: LEEDM.E.1990.0067.0015 (pictured below).

Current description:

black rayon(?) prayer shawl or tallit bag, plain with drawstring. Name tape inside reads "John Wartski". Contains wool prayer shawl, white with black bands;

There are three possible version of the additional information accurately describing the use of the tallit. Each would start: 'this is the traditional prayer shawl edged with twisted and knotted fringes known as tzitzit…' Followed by one of three alternatives below:

For an Orthodox community such as the UHC, the explanation would then say:

'In Orthodox congregations, men wear a tallit for morning prayers and Yom Kippur'

For Judaism as a whole the interpretation should read:

'In Orthodox congregations, men wear a tallit for morning prayers and Yom Kippur. In Reform and Liberal Jewish congregations, tallit may be worn by both men and women.'

References to Reform and Liberal practices may not be acceptable to an Orthodox Jewish Congregation and as the tallit has come from an Orthodox synagogue a more anodyne description would be:

'In the practice of Judaism, a tallit is worn for morning prayers and Yom Kippur.'

The literature read in support of this short project reveals a pervious reluctance of museum curators to engage with communities. The findings of this research demonstrate that by moving away from this isolationist approach, museum curators can have an opportunity to build their institution’s knowledge base about objects in their collections.

Written By: Alan Benstock

Image Credits: Alan Benstock