"Economies of Violence" - Report of a Symposium

Rhine ‘Toby’ Koloti is a Masters (M.Th) student at the University of the Western Cape, under the supervision of Prof. Sarojini Nadar. Rhine’s research interests are in the field of feminist theology and his thesis focuses on pastoral care responses to clergy sexual violence. Rhine is a member of the Desmond Tutu Centre for Religion and Social Justice and currently serves as the centres’ research assistant and an associate editor of the African Journal of Gender and Religion. He is also currently serving as the Anglican Students Federation’s Gender, Education and Transformation officer in the Anglican Church of Southern Africa.

By Rhine ‘Toby’ Koloti

August is a loaded month in South African memory, as we commemorate two significant historical events: the anti-apartheid women’s march which happened on 9 August 1956, and the recent Marikana massacre on 16 August 2012. These two events are a painful reminder of the ways in which “economies of violence” have and continue to sustain the indignity and poverty that women, people of colour and marginalised men in South Africa disproportionately experience. As part of the commemoration, the South African Research Chair in Religion and Social Justice, Prof Sarojini Nadar, and the Desmond Tutu Centre for Religion and Social Justice (DTCRSJ) convened a three-part symposium on the theme “Economies of Violence”, on the 1st August 2019. The symposium included a panel discussion on Law, Gender, and Religion with Pumla Gqola, Seeham Samai and Leigh-Ann Naidoo which was facilitated by Eusebius McKaiser, a celebration of the 10 year anniversary of the book A Man Who is Not a Man by Thando Mgqolozana, and a public lecture by Eusebius McKaiser on the theme ‘Marikana, Masculinities and Money’ with Zintombizethu Matebeni as the respondent.

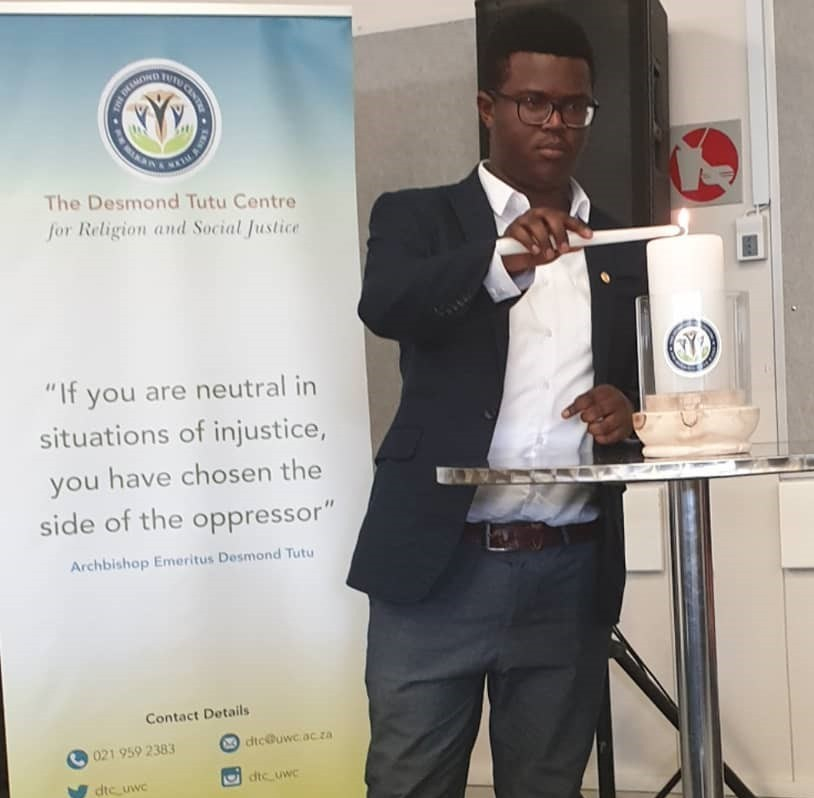

Rhine Koloti lighting the DTCRSJ candle in memory of the Marikana Miners

This event spoke to the DTCRSJ’s commitment to the indivisibility of justice and to the centre’s mission statement i.e. “...to facilitate ongoing debate and dialogue on the intersections of Religion and Social Justice through conferences, workshops, seminars, symposiums and other collaborations with civil society…”. But it was also a day which allowed me to reflect on my own research and personal commitment to social justice. As a research assistant, master’s student and as the Gender, Education and Transformation officer for Anglican students in Southern Africa, it challenged me to consider how my personal privilege, power and positionality impacts this commitment.

My master's project is focused on the responses of religious authorities to sexual violence. I was therefore intrigued by the panellist’s discussions on Law, Gender, and Religion as I was able to consider the ways in which religion and law are implicated in patriarchal violence and hierarchical gender binaries. However, it also brought moments of discomfort as panellists began to consider the idea of abolishing religion due to its deep involvement in the production, reproduction, and maintenance of sexual violence. I was unsettled because, while I am an activist for a gender-equal society without gender-based violence, I am also a Christian. And while I acknowledge that Christianity is implicated in systems of power such as heteronormativity, patriarchy, and androcentrism which produce economies of violence, my identity and meaning making system is also integrally tied to my religion - therefore abolishing religion would mean abolishing part of my narrative. Pumla Gqola mollified my discomfort by noting that religion and other social institutions need not be abolished, but because they have been developed within violent norms, it is those norms that have to be problematised and not the institutions themselves. Theoretically Pumla’s argument made sense to me however, I continue to wrestle with understanding how my religion can coexist with the notions of a non-gendered, non-hierarchical society while its key doctrines, Trinitarianism and Apostolicity, are embedded in hierarchy and power. I personally struggle with problematising my religions’ violent norms without the risk of being a heretic.

The 10th Anniversary celebration of ‘A Man Who is Not a Man’ also provided a moment for me to reflect on my relationship with literature. Pumla and Thando explored the common myth that black people do not read, let alone write. Thando pointed out that “black people do read however they do not have access to black literature”. This, for me, became a sad realization, especially because it reminded me of my own childhood schooling where we were constantly reading Shakespeare, Roald Dahl, and George Orwell due to the strategic ‘lack of black literature’. This influenced my thinking and imagination because I could only imagine stories as European or Western and if ever South African it would be the realities of white authors such as Sarah Penny. I therefore grew up believing that our stories are not worthy of being told in literature. However, Thando re-emphasised the fact that ordinary stories of people of colour are valid and worth telling too, hence he penned A Man Who is Not a Man. The idea of black people writing their own stories reminded me of Chinua Achebe’s words “Until lions have their own historians, the history of the hunt will always glorify the hunter”.

The University of the Western Cape Choir singing at the symposium

The final part of the event was a public lecture delivered by Eusebius McKaiser on ‘Marikana, Masculinities, and Money’. The lecture was introduced through two very symbolic yet saddening acts. Firstly, an air of discomfort was initiated when the University’s Choir sang the opening song, “Senzenina?” a struggle song which laments, “What have we done?” This performance was an emotive one and as I saw a choir member shed a tear, I was reminded about the senselessness of the Marikana massacre and how the killing of those men represented the personal loss and violence many South Africans experienced daily. The second act which added to the pathos of the moment was the recitation by, Lee Scharnick-Udemans, senior researcher in the DTCRSJ, of “A Poem for Marikana” by Gillian Schutte. This was read whilst I lit the centre’s candle in honour and memory of the fallen comrades of Marikana. The public lecture discussed ways in which toxic masculinities intersects with hyper-capitalism to displace, destroy and disempower people of colour and marginalised men in South Africa by dehumanising male labourers and humanising inanimate things such as ‘the market’. In response to this Ntombizethu Matabeni, spoke of the exclusionary and sexist nature of remembering the names and faces of the men that were violently killed in Marikana. This narrow view of men and masculinities in Marikana ignores women in mining, female masculinities and a deeper exploration of the realities in Marikana.

The Economies of Violence symposium allowed me to reflect, and encouraged me to consider the ways in which the intersections between religion, law, gender, class, and race play a role in the production of violence in my own research. I was also challenged, as a black Christian man, to acknowledge the privilege that comes with my identity and how easily that identity can be used to justify the “economies of violence” which continue to sustain indignity and poverty. Perhaps we are too quick to ask for the end of exploitative capitalism without seeing the need to undo the contemporary forms of patriarchy in our South African communities which so often coincides with our religious and cultural practices. To this, I agree with Mfecane that, as researchers, we need to find ways “to end this capitalist ethic of greed so that black African men become caring, sociable, responsible and averse to the use of violence, exploitation, and the sexual abuse of others as a means to proving their power” (Mfecane, 2018), perhaps that is our only hope.

Reference

Mfecane, Sakhumzi. 2018. (Un)knowing MEN: African gender justice programmes for men in South Africa. Pretoria: Centre for Sexualities, AIDS and Gender, University of Pretoria.

Our panellists from left to right: Eusebius McKaiser, Pumla Gqola, Leigh-Ann Naidoo and Sehaam Samai

1Sitting: Thando Mgqolozana and Pumla Gqola having a conversation on the 10th Anniversary of the book 'A Man who Is Not a Man'.